Common Infectious Diseases Click on any of the links below for more information. External Parasites Internal Parasites

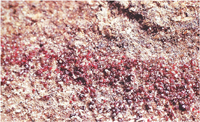

ParasitesAll animals carry parasites which have evolved to live on or in certain species, each species having their own type of parasite which may or may not live briefly on say, a human. Some of the parasites are benign and some are pathological. Keeping all parasites at a low level should be the aim of poultry keepers.Warmer temperatures are ideal weather for the proliferation of mites and lice with just a 10 day life cycle. If just the thought of crawly lice and biting mites makes you start to itch and shiver then imagine how the hens suffer from these pests, some of which can kill. External ParasitesRed Mite (Dermanyssus gallinae) (1mm long, red in colour when fed) This tiny bloodsucker causes anaemia in chickens and can pass disease on from hen to hen. It is nocturnal and sucks the blood of the hens at night, making it comparatively easy to control, if it is looked for at dusk. A whitish powder is sometimes the only betraying factor around the perch sockets and around cracks in the woodwork and eggs may have tiny blood spots on the shell. Red mites live in the hut during daylight and suck the blood of the birds at night causing anaemia, debility and sometimes death. Red mite can live for about 12 months without feeding and are then grey and very hungry.

Felt on the roof of the henhouse creates a sanctuary for red mite as they can crawl under there in the hated daylight and prove almost impossible to destroy, short of removing the felt. If it needs removing, either replace it with Onduline, which is a corrugated bitumen sheet and does not condensate as it is warm, or put corrugated clear perspex on instead, on top of the boarding. The light then prevents any red mite from breeding there. It is not possible to be sure of being free of them as jackdaws and other wild birds can bring them in at any time. Vigilance is the only answer. The life cycle of the red mite is horrifyingly short - ten days from hatch to breeding, especially in warm weather, so a small infestation can quickly get out of hand. Treatment Northern Fowl Mite (Ornithonyssus sylvarum) Northern Fowl mite is similar in size and colour to red mite but spends its entire life cycle on the bird causing anaemia and death. Crested breeds are particularly prone to infestation and if controlling the mites with permethrin-based powder make sure to sprinkle some down the ear canal as this is where they hide. DM (Biolink) can be used on the skin of an infested hen and may need to be replaced weekly for 3-4 weeks. Infested birds have dirty looking patches on them and are depressed. Exzolt controls this mite as well.

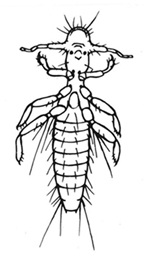

Common Chicken Louse (Menopon gallinae) This louse is flat, yellow, fast moving, about 2mm long, usually seen around the vent or under the wings but they move quickly out of the light as feathers are parted. This also has its entire life cycle on the bird and is host specific i.e. it won’t bite humans, and feeds on the skin and feather debris. It is not life-threatening, unlike the previous mites, but is an irritant and a heavy infestation can affect the performance of the birds when mating. This is mainly due to the clusters of eggs, looking like granulated sugar, which are laid at the base of the feathers under the tail. These can be a physical barrier to mating. Dusting with louse powder will control the louse and feathers with eggs on need to be removed and then the feathers and eggs disposed of safely, because just chucked on the ground they will hatch and get onto the next passing chicken. A heavy infestation can affect egg laying and make the hens appear listless.

Scaly Leg Mite (Cnemidocoptes mutans) Scaly leg mite causes intense irritation by burrowing under the scales of the leg, producing at first a whitish film and then mounds of white or pale yellow debris firmly attached to the leg. In severe cases the crusts can cut off the circulation in the leg and gangrene can set in. On a dark-legged bird, the beginnings of the white crusts can be easily seen. There is a musty smell (like mice) on the legs. Organic control is achieved by dunking the legs once a week for three weeks in a wide mouthed jar of surgical spirit, or putting a thick layer of petroleum jelly on the legs, which cuts off the air supply to the mites, but is rather messy. Scales, like feathers, are moulted once a year, so after the crusts have fallen off (the flesh is raw beneath so do not pull the crusts off), heavily infested legs may take a year to look normal again.

Depluming Mite (Cnemidocoptes gallinae) This may occasionally cause feather loss around the head and neck, but feather pulling is also a cause of feather loss in this area. Louse powder is not effective against these mites. Fipronil (Frontline) is not licensed for food-producing animals nor is ivermectin, these chemicals gets in to the eggs and should never be used. Internal ParasitesHelminths (worms) Gapeworm Capillaria Heterakis Ascarids

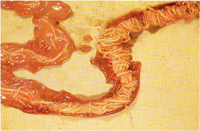

Trichostrongyles Tapeworm Gizzard Worm Regular use (prophylactic) of the only licensed product, Flubenvet, should avoid the situation where a bird is so infected with parasites that either impaction results, or when a large burden of worms is killed, the toxins they release kill the bird. Most intestinal worms have earthworms or insects as a transport host and wild birds are also carriers so outdoor birds are always at risk, although a certain amount of immunity develops. Stress can alter the delicate balance and allow the intestinal worms to proliferate. Heavily grazed or stocked areas should be rotated to avoid a build up of internal parasites. Flubenvet is available from agricultural merchants and vets for backyard flocks with no egg withdrawal time and should be used for 7 days, 3-4 times a year, more often if the hens are on the same patch of ground all the time. It is a powder, so if a little vegetable oil is put on the pellets first, this sticks the powder. Or feed may be purchased which has Flubenvet already added, but only purchase enough for each treatment to avoid the feed going nutritionally out of date. Aspergillosis All classes of poultry are susceptible to the Aspergillus fungus. It is a very difficult disease to treat successfully as there are few early symptoms and once it spreads throughout the airsacs, lungs, hollow bones and abdomen it is probably too late. Aspergillosis is the most common fungal infection in birds. Although birds are commonly exposed to the spores of this fungus, they develop the disease only under certain conditions. If a bird’s immune system is suppressed by a concurrent illness, malnutrition or stress, it may become sick after exposure. All hay should be suspected of harbouring the Aspergillus fungus, so should never be used as litter or nestbox material. Therefore, mouldy hay, straw, food or rotting or decaying vegetable matter, such as bark mulch, should be avoided as litter, as it is the spores of the fungus that are inhaled (wood chips are, however, not affected). Stress-induced Aspergillosis is frequently seen in birds subjected to surgery, reproduction, environmental changes, capture, confinement or transport. If a post mortem is done, the airsacs may have grey or white plaques and the normally pink lungs will be a dirty grey, but take care that the spores are not breathed in as this disease can be zoonotic, causing Farmer's Lung in humans. Most healthy unstressed birds will cope with a low level of infection, but birds under stress may die suddenly. It is also passed to the chick through the egg. Antifungal agents are successful if the disease is caught early enough, or the affected bird can be nebulized with F10, a modern disinfectant which kills bacteria, viruses and fungus but is not toxic to birds (www.f10biocare.co.uk) . Coccidiosis This is one of the most important poultry diseases worldwide and is ubiquitous, the only limit to the distribution of this disease is the distribution of the hosts. A protozoal parasite which multiplies in the gut, specific to different hosts. Not all species of coccidia are harmful but there are five of the Eimeria species pathogenic to chickens, five in turkeys, three in geese, three in ducks and three in pheasants. Enteritis (inflammation of the intestine) is present in all coccidia infections and usually accompanied by diarrhoea which may or may not have blood in it. Poor growth and impaired feed conversion is common and mortality can be increased. The infective oocyst (coccidia egg) is eaten by the bird and then multiplies over about 7 days within the gut, hundreds of thousands of new oocysts resulting from just one ingested oocyst. Dayold chicks do not get immunity from their mother. Birds of any age are susceptible, but most acquire infection early in life which gives them some immunity. Immunity is best kept strong by a low level of infection, which is what happens on free-range. Birds kept or reared on litter are more at risk when the coccidia has conditions which suit it such as wet litter. If the birds are also stressed by environmental factors (cold, overcrowding, poor ventilation) then disease results. The oocysts are very resistant to destruction, either by ordinary disinfectants or by drying out and can survive for months or years, oocide (egg-killing) disinfectants do work, however.

The species of coccidia have different areas of the gut which they prefer, some producing the expected bloody diarrhoea, some producing high levels of mucus, sometimes white diarrhoea, and others stunting growth. Infection can show from 3-6 weeks of age and infective oocysts can be transported by people looking after the birds. Older birds can become infected if either their immunity has been reduced due to being kept on a wire floor (no access to droppings and therefore no trickle infection) and then put onto litter, or if environmental stressors reduce their immunity. The birds generally look hunched and depressed with or without blood in the droppings. The addition of anticoccidiosis (ACS) drugs in the feed for only the first 6 weeks of life which reduce but not eliminate the numbers of coccidia has been the norm in order to let the chicks have a low level of infection and therefore acquire immunity. Avatec is probably the best ACS, avoid monensin as this is toxic to mammals. Permitted drugs in feed are, however, being reduced on an annual basis across the board. Resistance to some anticoccidial drugs has occured. Free-range reduces the incidence of disease while still providing trickle infection to boost immunity. Products currently licensed for treatment of a coccidiosis outbreak in chickens are based on amprolium. Baycox should not be used in hens laying eggs for human consumption. Temperatures above 56ºC and below freezing are lethal to oocysts, as is desiccation. Oocysts can stay in sheds despite disinfection unless a specific oocidal (“egg-killing”) disinfectant is used. By far the better treatment and prevention for chickens is the vaccine, Paracox. This contains all seven species of coccidia but these are weakened so that they cause the chicken to mount an immune response but not to become infected. As Paracox is an industrial product it normally comes in quantities to treat thousands of birds. It is available in small quantities from PHS Pharmacy (01845 577907). Paracox is administered once as a solution from a dropper bottle to a healthy dayold chick via its mouth. The shelf-life of the product is four weeks, so orders need to be made with the monthly expected hatch in mind. It is only available for chickens at present. Any feed used for vaccinated birds should not contain anticoccidial drugs as this will counteract the vaccine. The vaccine can be used on unvaccinated chicks up to 9 days old but is most effective at dayold. Infectious Bronchitis IB This coronavirus causes transient respiratory signs which are gone in a few days. The virus then locates mainly in the reproductive tract. Infection may show reproduction disease, mainly mis-shapen or shell-less eggs with watery whites. There is no treatment once the reproductive system is affected and such birds should be culled as they will infect others. IB is also implicated in egg peritonitis.

The virus is rapidly killed by common disinfectants, so good hygiene of feeders, drinkers and housing is important. New stock should be quarantined for 2-3 weeks. Prevention

Vaccine Marek's Disease Chickens from 6 weeks of age are affected by inhaling this herpes virus, symptoms are most frequently seen 12-24 weeks of age with the hormonal stress of point of lay being a classic time for the signs to appear. Older birds can sometimes be affected if stressors (changes in weather, food, handling, environment) are not minimised. Females are more susceptible than males. The most common signs are progressive spastic paralysis of the legs and wings. There is also an acute form where birds may die suddenly with no symptoms and tumours may be found in the liver, gonads, spleen, kidneys, lungs, proventriculus, heart, muscle and skin.

Control of the disease includes culling any affected birds. This increases the resistance to the disease in the surviving birds. Vaccination is feasible, especially if Silkies or Sebrights are kept. These are very susceptible to clinical signs of Marek’s and there would be few of these breeds seen at exhibitions if vaccination was not used. The vaccine is administered once by injection when chicks are ideally dayold or before 3 weeks old and is only available in 1000 dose packs, but is not expensive. In other breeds, using vaccine can hide the virus and so the whole stock gets progressively more susceptible (weaker) without any symptoms and if birds are sold without the recipient being told of the vaccination, the birds can pass on the virus to unvaccinated chicks, thereby bringing the disease to a flock which may have been free of it before. Mycoplasma A disease that has been known for at least 100 years. Mainly the respiratory system is affected and the disease may be becoming more common, spreading with increased travelling of stock, or it may be that we are hearing about it more with improved communications. The incubation period before clinical signs appear can be as little as a few days – it is very infectious. It appears to thrive in the bird when other pathogens are present, such as E. coli or infectious bronchitis (IB is certainly now more common in free-range flocks) or if the birds are stressed or debilitated. Debilitating factors include nutritional deficiency, excessive environmental ammonia and dust and stressors such as changes in the pecking order or exhibitions. The organism is passed on through the egg, so control in breeders is important. There is a vaccine but this only lasts for six months. Common signs can include foamy eyes, sneezing, nasal discharge, swollen eyelids and sinuses, reduced egg production and gasping. Mycoplasma synoviae: signs include swollen and hot joints in chickens and turkeys and/or respiratory signs as above, plus weak areas on the broad end of egg shells.

When nasal discharge is evident, feathers become stained with this as the bird tries to clean its eyes and nostrils. There is a particular sweet smell associated with this discharge which to the sensitive nose is immediately apparent when entering a hen house. A chicken can get an allergic reaction to shavings which causes foam in the eye, at shows there are usually one or two chickens that have this reaction. Antibiotic treatment will not completely cure the disease but will reduce the incidence to a tolerably low level. Tylan Soluble is licensed for the treatment of mycoplasma, as is Aivlosin. |